What's going on in Greece and why it matters

By Matt O'Brien June 28

At some point, the unthinkable becomes the inevitable (chắc chắn xảy ra). That moment — leaving the euro zone — may be coming for Greece now that its latest bailout battle (cuộc chiến cứu trợ tài chính cuối cùng) with Europe has degenerated into the fiscal equivalent of trench warfare. It's bad enough that Greece's ruling party, Syriza, has resorted to calling a referendum (/ˌrefəˈrendəm/ cuộc trưng cầu dân ý) next Sunday on whether or not Greeks should accept Europe's terms.

If Greece votes yes, there would probably be new elections and another bailout. But if Greece votes no, it would probably have to ditch (dừng) the euro and bring back its old currency, the drachma. In the meantime, though, Athens is closing the country's banks and preventing people from moving much money abroad in a capitulation to the panic gripping its financial system. That became its only option after the European Central Bank announced on Sunday that it wouldn't approve any more emergency loans to Greece's banks.

Chủ nhật tuần này là thời điểm để người dân Hy Lạp đưa ra quyết định cuối cùng là có chấp nhận hay không chấp nhận những điều khoản của Euro. Nếu chấp nhận, có khả năng sẽ có một cuộc bầu cử mới và một gói hỗ trợ tài chính khác. Còn nếu không, rất có khả năng Hy Lạp sẽ quay trở về đồng tiền cũ của mình, đồng drachma. Hiện tại, NHTW Hy Lạp đã dừng việc cấp vốn khẩn cấp cho các ngân hàng.

Now it might be hard to believe, but Greece and Europe really aren't that far apart on a deal. Europe wants Greece to cut its pensions more than it already has — which, in some cases, has been as much as 40 percent — but Greece wants to cut them only half as much and make up the rest with higher taxes on businesses. In other words, both sides agree how much austerity (khắc khổ) Athens should do, just not how it should do it.

Châu Âu muốn Hy Lạp cắt giảm mạnh chế độ phúc lợi, trong vài trương hợp lên đến 40%, nhưng Hy Lạp chỉ muốn 1 nửa số đó, đồng thời nâng thuế cho doanh nghiệp.

The problem, as it always has been, is the politics. Syriza insists that it has "red lines" over pension cuts it cannot cross, but Europe has quite literally drawn red lines through them and said, take it or leave it. This hard-line stance is more about warning anti-austerity parties in Spain and Portugal that there's nothing to be gained from challenging the continent's budget-cutting status quo as it is about the 1.8 billion euros in pension cuts — not even a rounding error in the context of Europe's economy — that it wants from Greece. Both sides feel like they can't negotiate any more, so they're not.

So now, to use a technical term, all hell is about to break loose. The immediate problem is that, without a deal, Greece doesn't have the cash to pay the International Monetary Fund the 1.5 billion euros it's supposed to on Tuesday. So it will likely default, or, to put it a little more politely, be "in arrears (khất nợ)."

The bigger problem, though, is Greece's banks. They're already in a precarious (hiểm nghèo) enough position that they need ECB-approved emergency loans just to stay afloat. But if there isn't an agreement, then the current bailout will also expire on Tuesday — Europe ruled out any kind of extension — and the ECB's self-proclaimed rules would prohibit it from allowing any more loans to Greece's banks. And so the banks had no choice but to close after this, in fact, happened.

Now it's worth pointing out that the ECB does really have some discretion here. This is only a rule it's given itself. If it wanted to, it could keep authorizing more loans for Greece's banks, at least until the referendum. But it doesn't want to. It's already announced that it won't allow any more than the 89 billion euros of emergency loans it already has for Greece's banks. About the only consolation (an ủi) is that the ECB says it "stands ready to reconsider its decision" if, reading between the lines, Greece backs down and accepts Europe's offer.

The result is that Greece's banks are facing their own financial crisis. There's been a slow-motion bank run the past few months — a bank jog, really — that's picked up pace the past few days as it's looked like there wouldn't be a deal. After all, even in the best-case scenario that there was only going to be a bank holiday, it makes sense to take out whatever money you might need in the next week or so. But in the worst scenarios, like a euro exit or bank bail-in where deposits are taken away, the rational thing is to pull all your money out as soon as possible. If you didn't, then your old euros might either get turned into new drachmas that wouldn't be worth anywhere near as much, or get expropriated to fill the hole in your bank's balance sheet.

These low-level worries have turned to outright panic, though, with all the uncertainty around the referendum. Greeks swamped (làm mất tác dụng) their ATMs on Saturday to get as much money out as they could ahead of the vote. It was enough that, according to Reuters, more than a third of the country's ATMs ran out of cash at some point during the day. It's no surprise, then, that the government will close the banks on Monday and keep them closed for at least a few more days after that. They would fail otherwise. Not only that, but the government will stop people from moving their money out of the country — what economists call capital controls — to try to ease some of the strain (trạng thái căng thẳng) on the financial system.

These aren't exactly ideal conditions — closed banks and a debt default — for holding a vote on your country's economic future. But then again, if the euro were working, there'd be no need for a plebiscite (=referendum) on it. And make no mistake, that is what the referendum is about. If the Greek people vote no, like their government will, then there won't be any more ECB loans or bailout money coming, and the only way to get the money their banks need would be to print it. Greece doesn't have money to print, though. It has the euro. So it'd have to get rid of the common currency and bring back the drachma.

Nếu người Hy Lạp không đồng tình với điều khoản của Châu Âu, sẽ không có bất kỳ khoản tiền cho mượn nào của ECB hoặc viện trợ tài chính nào đến nữa, và cách duy nhất để lấy tiền cho ngân hàng là in tiền. Tuy vậy, Hy Lạp không có tiền để tin. Ngân hàng có Euro, do vậy, phải lấy EURO đổi ngược lại đồng drachma.

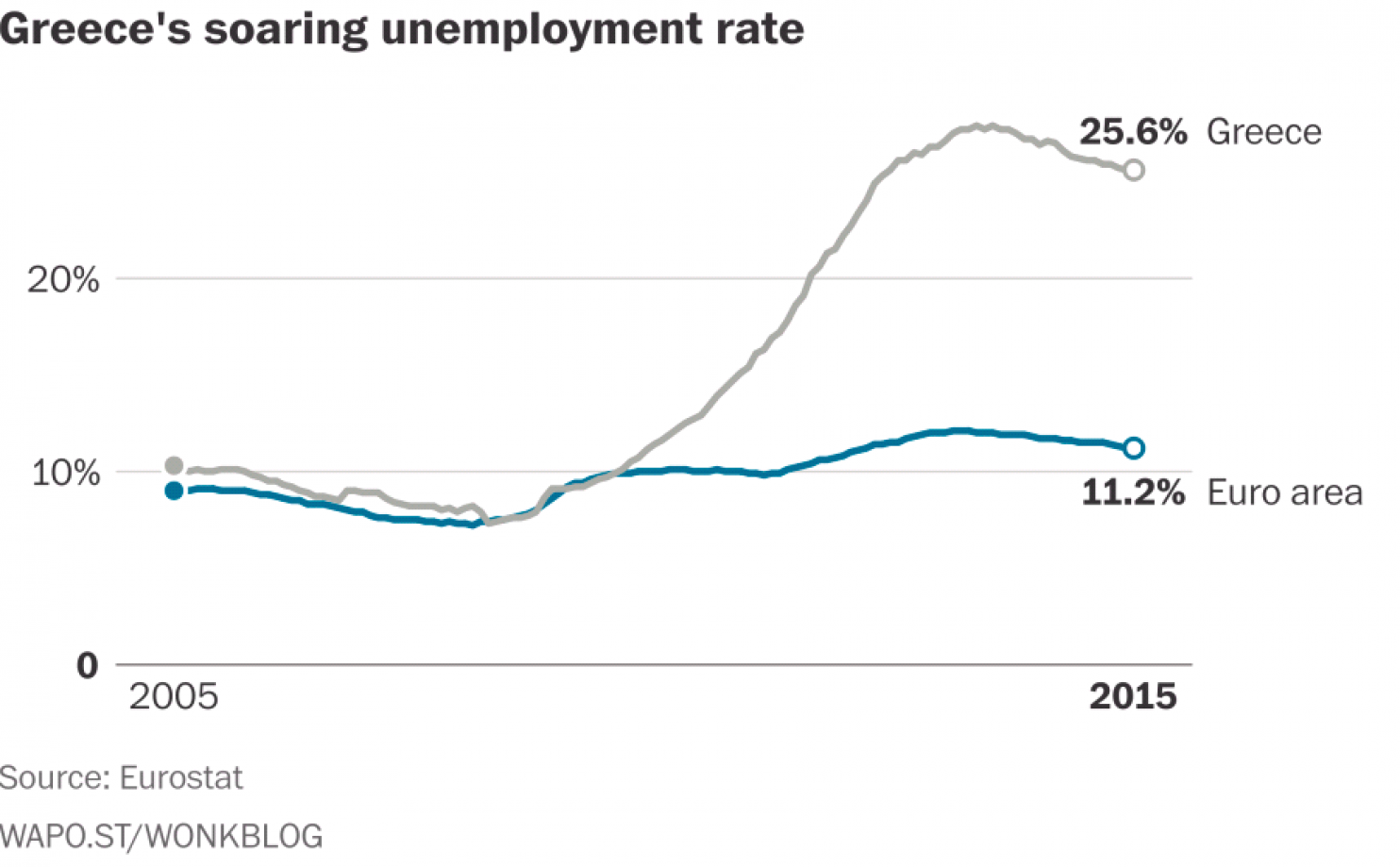

Now, it seems hard to believe things could get any worse for a country with 25 percent unemployment, but, in the short-term, they would. The new currency would plummet (rơi thẳng xuống), inflation would jump into the double digits, imported essentials like gas and food might need to be rationed, businesses that borrowed in euros would default, and the government would have to balance its budget immediately. Why would Syriza do this? Well, because it would move the economic light at the end of the tunnel into the middle of it. In a year or two, this pain would pass and Greece would be left with a cheaper drachma that would make its exports more competitive and its tourism more attractive. The economy would start to recover, and fast.

Thật không dễ tin thêm những khó khăn nào nữa sẽ đến với 1 quốc gia đang có tỷ lệ thất nghiệp 25%, nhưng trong ngắn hạn điều đó sẽ đến. Đồng tiền mất giá, lạm phát phi mã, buộc phải hạn chế nhập khẩu hàng hóa thiết yếu như gas và thực phẩm, doanh nghiệp đang vay mượn Euro sẽ phá sản, chính phủ phải cân đối ngân sách ngay lập tức. Nhưng nếu đi theo hướng này, người Hy Lạp sẽ sớm nhận thấy ánh sáng cuối đường hầm, trong 1 hoặc 2 năm, nỗi đau sẽ qua và đồng drachma rẻ sẽ giúp nhập khẩu và du lịch tăng trưởng. Nền kinh tế bắt đầu phục hồi và tăng trưởng.

But if the Greek people vote yes, like the polls suggest they might, then it'd be more of the same. Austerity would continue, and the recovery would likely be nasty (kinh tởm), brutish (đần độn) and long. About the only difference is that Greece might be reduced to being a once and future full member of the common currency, like Cyprus was, with euros that weren't quite euros but weren't quite not euros, since they probably wouldn't be allowed to take them anywhere outside the country. Well, that and the fact that they'd need a new government. Europe doesn't trust Syriza to implement any kind of austerity agenda and would either demand or force Greece to call new elections.

Nhưng nếu Người Hy Lạp chấp nhận điều khoản của Châu Âu như 1 khảo sát gần đây, họ sẽ vẫn vậy mà thôi. Quá trình thắc lưng buộc bụng sẽ tiếp diễn và phục hồi sẽ chậm chạp, kéo dài.

The real problem is that Greece's people want the euro, but they don't want the austerity that goes with it. That's why, even though it might seem irresponsible, the referendum may serve a good purpose if it puts an end to this incoherence. But the question now is whether there will even be anything to vote on next Sunday. That's because Europe says it's going to pull its offer Tuesday night. That's its way of trying to pressure Greece into canceling the referendum by making it pointless. And it might work. It did the last time a Greek government called for one back in 2011. History might repeat itself, first as tragedy and then as farcical tragedy.

If Greece does leave the euro, though, it will in large part be because Europe thinks that Pandora's Box is empty. In other words, nothing bad would happen to Spain or Portugal or France or Germany. Why wouldn't it? Well, Europe bailed out the banks that had lent money to Greece under the guise of bailing out Greece itself, so there shouldn't be any contagion to the financial system. And the ECB has not only begun buying other country's bonds, but also promised to buy as many as it takes to keep their borrowing costs down, so there shouldn't be any contagion to the other crisis countries, either. That's all true, but it might not be true enough. As long as Greece is part of the euro, Europe can punish it for any perceived fiscal sins as a warning to everyone else: Do as we say, or suffer. But if Greece leaves and then recovers quickly, that lesson will be lost.

The euro was supposed to be irreversible, just like the Titanic was supposed to be unsinkable. It helps if you try to avoid the icebergs, and not insist that you can survive them.

Source: washingtonpost.com, finandlife dịch